Book of Knowledge

Chapters: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

List of all languages referred to in the Book of Knowledge and other sections of the website.

DOWNLOAD and print out the Book of Knowledge.

Let’s Revise! – Chapter 10

Go to the Let’s Revise section to see what you can learn from this chapter or test how much you have already learnt!

Chapter author: Katarzyna Klessa

Some methods of language documentation

Elements of documentary practice

- Preparatory steps

- Recording equipment and session set-up

- Processing and analysing data

- Example on-line archives for endangered languages

- Legal and ethical problems

Appendices: More about the history of sound recording, data formats and structures

References

Useful links

What is language documentation, how is it done, and why is it important?

One of the important needs of humans is the desire to preserve the memory of the most meaningful achievements of their lives and to pass on the knowledge about their times, cultures and civilizations to the next generations. Over the centuries, people have developed various ways of transmitting knowledge from generation to generation based on oral tradition (oral culture) and written texts. Because of this, it is nowadays possible to track back and explore even quite distant history, as well as the history of language. An exception is the sounds of language, since it was impossible to preserve the sound of speech of our ancestors until not fairly recently: the first recordings of a human voice that we can listen to are dated only to the second half of 19th century and are therefore very ‘young’ compared to the most ancient written documents reaching back many centuries in the past.

In this chapter, we will look at issues related to the preservation and use of information about languages. We will particularly focus on endangered languages and on the possible reasons why they should be dealt with in a special way. Some of the suggested reasons are listed in the box below.

WHY DOCUMENT ENDANGERED LANGUAGES?

- To preserve human cultural heritage in general;

- To keep memory of the facts important for the local communities, families, individuals;

- To better illustrate linguistic theories with real-life observations of languages in use;

- To study language contact [1].

Language documentation comprises the collection, processing and archiving of linguistic data – for example, texts, word lists, recordings of conversations, videos where people tell fairy tales, etc. While people interested in languages have carried out such activities for centuries, the new technologies of our times, but also advances in linguistics and neighbouring fields, have led to considerable changes. Today, documentary linguistics is a new, ‘hot’ branch of linguistics where researchers with very different profiles and interests are working together: some travel to remote places of the world to collect data from lesser known and endangered languages, others think of new ways to process and store huge amounts of multimedia data, still others use language documentations for revitalizing endangered languages, for example, by preparing dictionaries and teaching materials.

THE ADVENTURE OF DOCUMENTING ENDANGERED LANGUAGES

In 2008, two American linguists active in documenting endangered languages made a film where they show how interesting, sometimes how dramatic and sometimes how funny their work can be [2]. Find information about this film (“The Linguists”) and additional materials on their website! www.pbs.org/thelinguists

The trailer is also on YouTube here

The documentation of endangered languages is an especially important and urgent task if we want to at least preserve some of the wealth that these languages possess and that otherwise will soon be gone forever. Having said that, documentary linguistics is not only concerned with endangered languages, and many issues, for example, issues concerning recording speech, transcribing spoken data, or building corpora, are the same for all languages. However, smaller, less studied and especially endangered languages also provide special challenges – first and foremost with respect to the amount of available data. If you want to document one of the larger languages such as English, Chinese, German, Hungarian, Dutch, Polish, etc., you can rely on already existing data and quite easily find samples of written and spoken language from which you could build up your documentation: books, newspapers and other written documents from the past and the present, many of these already digitalized, television and radio shows that can be recorded or simply downloaded from the Internet, language used in Internet forums and other social media, and many more. Because computers, the Internet and recording devices are widely available, the amount of such data and its accessibility is growing rapidly. For endangered languages, the situation is often completely different. Many of these languages do not have a written tradition and written data may be completely unavailable or sparse, the languages are not used in the media, or their speakers do not use the Internet (and if they do, they often use another language). In such cases, linguists must start from scratch and collect as much data as possible by recording speakers of a given language. Ideally, language documentation contains representative samples from different speakers – representing different age groups, different professions, of both sexes, and different origins –, but in the case of endangered languages this may not be possible, because the number of speakers is too small and/or there are only elder speakers.

An important issue apart from the number of speakers and amount of data concerns the communication between the linguists or other researchers who want to document a language, and the language community. In the case of endangered or minority languages, the documenters often are outsiders, not members of the community. They may not be fluent speakers of the language in question and can communicate with the speakers in a second or a third language. This often leads to an unnatural use of the language that is to be documented. The documenters may not know all the customs and the culturally and socially right ways to behave. Without wanting to, they may act in a way that is considered impolite or patronizing to the community. It is therefore always better if the documenting team includes members of the local community. This will not only improve the quality of the language documentation, but it is also a question of principle – after all, it is their language! For the researcher, a recording of an old man speaking about his childhood may be “data”, but for a member of the community – for example, for the granddaughter of an old man, this recording may be something very personal, like a treasured family remembrance.

Thus, language documentation fieldwork is often a lengthy process during which documenters need to travel, establish new contacts, integrate with the local community, become familiar with their customs, habits, and culture, before they can begin the actual work.

DOCUMENT A LANGUAGE OR DIALECT – AN EXAMPLE

Go to the section What Can you do? – Document a language or dialect. and listen to Tymoteusz Król talking about his experiences with documenting Wilamowicean, one of the smallest minority languages spoken in Poland. Can you think of a small language or dialect in your region? Have you heard of any recordings, videos, TV programmes or books about or in that language?

More than just words and sentences

In the preliminary definition of language documentation given above in this chapter, we mentioned three elements of language documentation: collecting (recording, taking pictures, gathering written documents, etc.), processing (analysing, systematizing, transcribing, translating, etc.) and storing (archiving) data. These elements can be thought of as three successive steps. For example, first we record words, than we translate and analyse them, and the result, for example in form of a word list or a small dictionary, is stored in print or electronic form. However, the three steps are more intertwined. There may be overlapping – for example, transcribing (writing down) spoken data can be considered an instance both of collecting and of processing of data, and even as a kind of archiving. Furthermore, it is often necessary to “look ahead” and already think about possible ways of analysis and archiving from the very beginning, before starting any work. For example, when researchers are interested in the sound system of a language, they will probably first collect a small sample, then do some preliminary analysis in order to learn about the basic phonetic rules, and then collect more data more purposefully. Researchers interested in phonetics may also have different expectations concerning the kind of data collected and the way it should be archived than researchers with a primary interest in cultural traditions. Nevertheless, it is regarded as important to maintain the distinction between data collection and analysis. The same set of source (or “raw”) data, when properly constructed, can serve as a resource for various types of analyses conducted by researchers specializing in a wide range of fields such as: linguistics, cultural studies, sociology, psychology, history or geography. One of the researchers might look for typical linguistic features (e.g. syntactic structures or phonetic characteristics), another would be interested in social relationships reflected by the material (e.g. the functions and roles of speakers within a community). They will apply different methods, but use the same set of data. Language documentation should therefore be seen from an interdisciplinary perspective.

This perspective leads to a broader view of what is the object of language documentation. Rather than collecting words and sentences, linguists have to document linguistic practices and traditions that exist and can be observed within a community. These linguistic practices and traditions are manifested by [3] [4]:

- linguistic behaviour: everyday conversations, language use in social contacts between community members, linguistic customs and traditions (cf. the section “Language is doing and culture is a verb” in Chapter 6 on language and culture);

- the speakers’ knowledge about their language: what speakers know and can explain about the rules and structures of their language (after Himmelmann 1998: 161-195), another thing of interest might be the speakers’ ideologies – what they actually think of their language, are they convinced that it is worth preserving, and what they actually do in order to maintain it (e.g. whether grandparents use the language while speaking to their grandchildren?).

Based on these definitions, the aim of documentation is not just recording the sounds of language as such, but recording the sounds of language as communicative events [3] [5]. A communicative event includes more than speech, and to understand what is going on we also need information, for example, about gestures, face expressions, the broader situational context, the presence of third parties, or artefacts used at the time of the recording.

Data and metadata

Briefly speaking, metadata can be defined as data describing other data or even simpler: data about data.

For example, the basic type of data for a phonetician will usually be acoustic data derived from a sound file together with its transcriptions while the accompanying metadata may include various types of information about the speakers (such as their sex, age, region and community of origin, health condition, social and family status), recording conditions (environment, background noises), technical properties (equipment, software, quality), authors(s), etc. However, the distinction between data and metadata is not always obvious because metadata can in fact become data and vice versa, depending on the aims of the study. In our example, the phonetician could treat the region of origin as data and not as metadata in case when he/she wanted to study regional variations of pronunciation. Furthermore, if the same corpus were to be analysed by a culture anthropologist, then the focus would likely shift to the description of family relationships and social information which would consequently be treated as data rather than metadata.

Some methods of language documentation

Documenting communicative behaviour and language in use

Until about the middle of the 20th century, the idea most linguists had of language documentation was a dictionary, a grammar, and a collection of texts, preferably fairy tales or other narrative texts. Much documentation like this had been carried out already during the 18th and especially the 19th century, and the results are still useful for linguists today. As an illustration, you can listen to a recent recording (2013) here and look at the transcript and translations of a fairy tale first documented in 1895 by S. Ulanowska [6].

However, today we feel that something is missing in these older documentations, something that was difficult or impossible to document in an area where the only means of documenting was writing and drawing. As discussed above, language documentation assumes not only a description of particular elements of grammar and vocabulary, but its central issue is documenting the language in its natural environment, including the characteristics of the speakers, their mutual relationships and the situation in which they live.

When looking at the technical quality we must yet admit that the best recordings can be obtained in an anechoic chamber of a recording studio rather than in the language’s natural environment. Noise can be controlled and minimized in the studio, and we may precisely adjust the types and positions of microphones or video cameras in advance, so that even the slightest details will be appropriately recorded. Such recordings are especially valuable for subtle analyses of the sound system of a language, and that is why anechoic chambers are usually situated in departments of phonetics at universities and research laboratories (see an example list of such laboratories and departments here)

Studio recording environment: recordings in an anechoic chamber, the Laboratory team at work, equipment (the Laboratory of the Psycholinguistics Department, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, photos: Agnieszka Czoska (left, middle), Maciej Karpiński (right)).

Language documentation thus faces a compromise between quality control and natural environment requirements. By definition, it is practically impossible to capture most real communicative events in an artificial surrounding of a studio. This may be particularly true for elderly speakers who sometimes are the only speakers left of a severely endangered language (cf. UNESCO’s “Levels of endangerment” discussed in Chapter 8 of the Book of Knowledge). On the other hand, recording speech outside the studio usually means difficulties in achieving good quality, even if we use excellent recording devices. When we sit in a room and chat, we usually don’t pay attention to small background noises, but when we listen to a recording of that conversation we suddenly discover that there was a clock ticking or a fridge buzzing!

Listening exercise

Listen to the following recording of utterances in the language Teop: click here

What were the conditions under which this text was recorded? What kind of background noises can you hear?

Find Teop on the Interactive Map where you can listen and learn more about the language and the recordings you heard in the exercise above!

Speakers who are recorded (even in a very friendly environment) usually pay more attention to their way of speaking and consequently modify their linguistic behaviour: their speech can change in a quite unpredicted way. For example, it can become more/less formal, more/less polite or politically correct which can be manifested by changes in phonetic-acoustic parameters such tempo, intonation, intensity, timing patterns, pausing schemes, and others. This is related to the so called Observer’s Paradox.

OBSERVER’S PARADOX

The aim of linguistic research in the community must be to find out how people talk when they are not being systematically observed; yet we can only obtain this data by systematic observation. [7]

Many experiment set‑ups have been designed with a view to obtain data on varying speaking styles and levels of spontaneity. In case of large and well-documented languages, a wide range of corpora have so far been collected using either the existing recordings or creating corpora from scratch. Existing recordings can include, for example, television shows or parliamentary speeches. However, as you can imagine, communication in front of TV cameras, lights, and microphones is quite specific and not always suitable for documentation or research needs.

A method half-way between collecting spontaneous speech and eliciting data after a fixed scheme is to set up a certain scenario for a dialogue between two speakers of the language to be documented. For example, one part of the Kiel Corpus of spoken language [8] was created by giving two speakers a different time table each and asking them – using a fake telephone line – to make an appointment that would fit both. The result was short spontaneous dialogues with a limited and largely predictable vocabulary.

An interesting example is also the JST/CREST database of spontaneous and expressive speech [9]. This database consists of several subsets one of which was collected by volunteering speakers wearing small portable recording devices and recording their own spoken communication during their daily activities (home, work, school) for a relatively long period of time (e.g. several months). The speakers could switch off the device at any moment as well as decide whether any part of the recorded material should be excluded from further analysis. The experimenters assumed that after some time speakers would become familiar with the recording equipment to the extent that they would stop paying attention to the fact of being recorded and thus their behaviour would become more (or even fully) spontaneous. However, a potential drawback in this case might be related to the fact that the recordings took place in varying locations characterized by unpredictable noise levels and thus cannot be fully controlled for quality. Another drawback concerns the metadata – it may be difficult to keep track of all the conditions of the recorded speech event (participants, context, etc.). And of course there are copyright issues, the question of personal data protection for all participants, not only the one who had agreed to participate in the experiment (see below the section on ethical and legal issues).

STUDY QUESTION

Think of a recording scenario that would possibly enable producing good quality audio/video recordings of spoken communication of (a) children, and (b) elderly speakers, without losing too much of the spontaneity of speech.

Note: there might be many competing scenarios.

In the case of endangered or minority languages, the choice of materials is often very limited so almost any type of data might be a source of valuable information. It is worth remembering, however, that in order to make further analyses and descriptions easier we ought to work on the data thoughtfully and carefully rather than to “(mindlessly) collect heaps of data without any concern for analysis and structure”, as Nikolaus Himmelman put it [10]. In other words: if you have access to an endangered language (for example, a dialect your grandmother speaks), you may of course just make a quick recording with your smartphone and put it onto YouTube or other website (and if you surf the Internet you will see that many people do just that) – but this is not how professional language documentation is done.

Documenting what speakers know

Documenting endangered languages, fieldwork conditions: Yurakaré (left, photo: Sonja Gipper & Consejo Educativo del Pueblo Yurakaré) and Tahuatan (right, photo: Gabriele Cablitz).

As important as the documentation of linguistic behaviour in a natural setting is, it is often not enough to get a comprehensive picture of the language. This is because speakers always know much more of and about their language than they show in their linguistic behaviour. In the course of natural conversations or interviews, the coverage of vocabulary items and structures depends on the topic of a particular conversation and usually reflects the items most frequently occurring in everyday use of the language. Less frequent words or structures may not come up at all even when many hours of spontaneous speech are recorded. If documentation is based solely on such material, the range of vocabulary and constructions is always a matter of chance. For example, if you happen to record a conversation about how many children there are in various families and how old they are, you may get many examples of numerals. In other recordings there may be no single numeral, but maybe many words for colours, and so on. Researchers interested in a special topic (numerals, colour terms, names of animals or plants, words for body parts, prepositions, etc.) will not wait until these items happen to come up in spontaneous discourse, but will use other methods of data collection, i.e. elicitation (elicitation is a term frequently used to designate the collecting of desired types of data directly from speakers, according to a previously designed scenario rather than using only what is available at the moment).

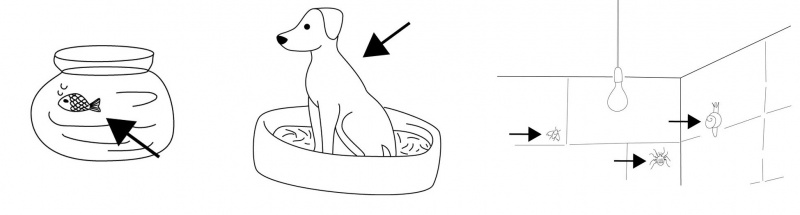

A common way to elicit vocabulary is to use a list of words that have to be translated into the language being documented. For documenting basic vocabulary, the Swadesh list is often used (see: Swadesh lists given in Chapter 2). Using translation as a method for elicitation however has many drawbacks. Not all words can be translated between two languages, and words that have no equivalent in the source language (for example, English) will not be discovered by this method. Therefore it is often better to use pictures, props or artefacts to elicit specific vocabulary items. Pictures and props are also very useful for eliciting grammatical structures, for example, to find out how spatial relations and motion are expressed (how you say things such as The cat is on the map, The cat is climbing the tree, The apple fell from the tree). There are already special sets of pictures and other stimuli available for several purposes. Story builder [11] is an example for such a set that is freely available on the Internet and can be used to elicit many different structures, especially constructions with verbs. Another example is a ready-to-use Field Manuals collection [12] where you can find pictures for eliciting vocabulary related to location of objects in space such as those shown in the picture below [13].

Mutual location of objects in space. Example TPRS (Topological Relations Picture Series, Bowerman et al., 1992, the complete source set of pictures at: fieldmanuals.mpi.nl/volumes/1992/topological-relations-picture-series/)

When you download the pictures usually you also obtain suggested instructions for the recording scenario and terms of use (see for example materials for route description elicitation: fieldmanuals.mpi.nl/volumes/1993/route-description-elicitation/ or a body colouring task: fieldmanuals.mpi.nl/volumes/2003-1/body-colouring-task). It should be taken into account, however, that not all pictures are universal and some of them cannot be useful because of cultural differences (e.g. dogs or representations of humans in Muslim cultures).

A method for eliciting coherent text after a given scheme is to show a mute film or, especially with children, a comic book or picture book without text and ask the speakers to retell the story in their own way. The most famous film in linguistics is The Pear Story [14] – this story has already been told in very many different languages, and the text thus collected can be compared and analysed for various aspects of grammar.

Linguists who are primarily interested in the sounds of language and not in collecting new words or constructions may also ask speakers to read aloud prepared and specially designed lists of words or short texts. An example for such a text is Aesop’s fable: The North Wind and the Sun commonly used by phoneticians and phonologists to illustrate the sound of languages (cf. Handbook of the International Phonetic Association

[16]). (see Chapter 2 and Chapter 4). Of course translating the text to some languages may be difficult because not all words or structures always have their direct equivalents in the language. Another problem might be the simple lack of a (commonly known) written form of the language making it impossible to design a reading task.

LISTENING

Listen to the recordings of The North Wind and the Sun Aesop’s fable in three languages. Pay attention to the technical quality:

- Polish – click here to listen (speaker: Ewa Sobczak, a professional actress [15])

- Latgalian – click here to listen (speaker: Evita Kozule, a student of a linguistic faculty, recorded by K. Klessa & N. Nau

- Halcnovian – click here to listen (speakers: Fryderk Hanusz, Józef Jancza, source: [6b]

Note: Halcnovian is a critically endangered language: according to recent records it had only 8 speakers in 2013. Furthermore, it does not have a written tradition, so in this case the text of the recording was not read in Halcnovian, but translated from a model written in Polish.

Find Latgalian on the Interactive Map!

If one wants to document what speakers know about their language, it is of course also possible to ask them directly (though this can never be the only or the main method of gathering data). For this purpose it is useful to collect the terminology that speakers of a certain culture use to speak about language – do they use equivalents to English words such as word, sentence, syllable, past tense, and so on, or do they have other categories? This brings in the possibility of speaking about a language in this particular language instead of using a third language for descriptions.

Elements of documentary practice

As defined above, language documentation comprises the activities of collection, processing and archiving of linguistic data. When we consider that language documenters often need to travel a lot in order to collect their data and then they have to safely store, process, and share that data, we can easily understand a strong link between language documentation and technology. Some years ago, when a standard recording device was quite a weighty and sizeable machine, the task of a documenter was much more challenging than today, when you can carry a high quality audio or video recorder in your pocket.

Thanks to technological developments the work on data has gained an unprecedented efficiency and speed. For example, it is now possible to search a piece of information through millions of vocabulary items over a time shorter than a few seconds or to store high-quality videos or sounds on a one-centimetre portable device (while a similar amount of data would once have needed a few rooms in a building of dozens or even hundreds of square metres of capacity). Moreover, people can make their data available to a wide audience practically at any moment. The Internet is abundant in various types of information.

LEARN MORE

If you want to learn more about the history of speech recording, reproduction and storage, see the Appendix 1 to this chapter.

However, together with this great potential, new challenges and questions emerge. For example, it can become more problematic than before to organize or even search through data, to avoid chaos and control data access by various users and as well as to account for all legal and ethical issues (see below).

Preparatory steps

The preparatory steps preceding the actual data collection may include contacting speakers, getting familiar with the so far available materials, planning recording scenarios, testing software and equipment, choosing file formats or defining file naming conventions.

When you already contacted the speakers of the language to be documented, it is a good practice (and often a duty (read also about some legal and ethical problems) to ask for their formal agreement to the recordings, and to take care of their positive attitude and willingness to participate. Endangered languages are often spoken by small communities, where the family and other social relationships may play even bigger role than in larger and thus much more diversified language communities. The attitude of the local community can be really crucial in such case, and their rules and internal laws have to be taken into account. – Is it all right for a stranger to walk around, take pictures of houses and sacral places and record people’s speech? – It is always better to ask first before doing such things. Some communities explicitly state that permission has to be granted before pictures are taken (see for example [17]).

STUDY QUESTION

What could be the reasons if a speech community does not want external researchers to make video films of speakers and their homes? What could be done to resolve a conflict of interests between the researchers and the community?

Another useful step to be done in advance is to decide about ways to organize your data, e.g. think about where to store the data, how to make backup copies and how to name your files and folders. Making such plans is already a preparation to data analysis because afterwards it will help you to classify and describe your data.

HOW TO ORGANIZE MY FILES / FOLDERS?

When you are about to work with a number of files, one of the crucial steps is to decide about file naming conventions, preferably before starting data collection. Think of the elements that should be included in the names of files or folders. Maybe some of the following:

- date of creation (although usually the date is encoded in the file header, it might be convenient to have it also in the file name for your convenience)

- speaker’s ID

- type of data (speaking styles, registers, environment…)

- other?

What should be the order of the elements? Remember that you will probably wish to sort your files by names. You can use abbreviations or codes in the file names to make the names shorter. Otherwise, you may wish to name your files only with unique ID numbers and include information about the contents in additional information files.

- In case if you want to deposit your data to an existing repository such as DOBES [18], it would be best to first visit their website, check about recommended conventions and use them from the beginning of your work, e.g. [19]

- To explore some of the other existing file formats and standards, see e.g. [20].

In the case where you do not produce new data but rather deal with already existing archives (for example digitize historical data or transcribe old recordings), an important step will be to preserve the original naming conventions and other information related to the source materials. Keeping this information can be very useful in case you or someone else would like to go back to the very first version of the data.

Recording equipment and session set-up

Before choosing from many available types of audio recorders, photo and video cameras, recorders or microphones, you should consider their parameters and prices as related to your specific needs. The influencing factors can be the type of recording scenario, recording modalities (audio/video), the location for the recording session (“session” is a term usually used to name all the recorded events) as well as the characteristics of speakers such as age, sex, social status, etc. A crucial technical question is whether the equipment will be used on a stationary basis or rather for fieldwork, requiring travels. In the latter case, the critical parameters are its size and weight but also the power supply solutions, the availability and type of batteries, charging options, the shake resistance etc. Microphones can be embedded in various types of devices (such as portable recorders) or used externally, and connected with cables.

STUDY QUESTION

Think of a list of factors which could influence the choice of your fieldwork equipment, considering that:

- you need to travel by plane to the destination region

- your task is to document a language spoken in a couple of villages, not very distant from one another, and you will use a bicycle to travel between them (carrying your equipment)

- you will have a limited access to the Internet and will need to 1) backup your data in the meantime, 2) occasionally send samples of your data via a slow Internet connection

Dynamic (left), condenser (middle), condenser head-mounted (right) microphones (photo: Maciej Karpiński).

Two main types of microphones are distinguished according to their construction: dynamic and condenser microphones. Condenser microphones are often used in radio and TV studios, they are characterized by higher sensitivity and can capture a variety of complex sounds, including subtle background noises. A variety of condenser microphones is also used in cellular phones and the cheapest recorders but these are built with a different technology and their quality is incomparably worse than that in the more expensive models. All condenser microphones require an additional power source which may be a disadvantage in the case of fieldwork. Dynamic microphones can be used without any additional source of power which makes their usage simpler. They are characterized by a lower sensitivity as compared to the condenser microphones (which can actually be an advantage when the recording session takes place in a noisy environment) and are very useful for speech recordings, especially when the speaker speaks directly to the microphone, from a close distance. Dynamic microphones are also commonly used by singers during live concerts, while condenser microphones are usually used for recording vocals in an anechoic chamber.

STUDY QUESTION

Think of 2 or 3 recording locations and scenarios for a recording session. Consider the environment and the number of speakers. Which type of microphones would be better for these sessions?

Processing and analysing data

A step usually following data collection is creating a backup copy of the data in the original form, without any modifications. Backup copies can be stored on CD, DVD, blu ray discs, local or remote hard disks or small-sized portable storage media such as pendrives or memory cards. After ensuring that the backup copies are safely stored, the data can be analysed and/or further processed.

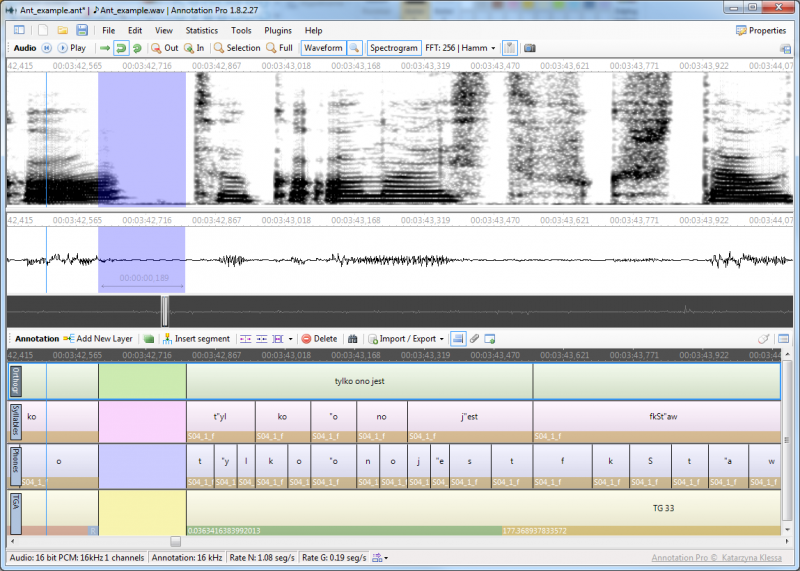

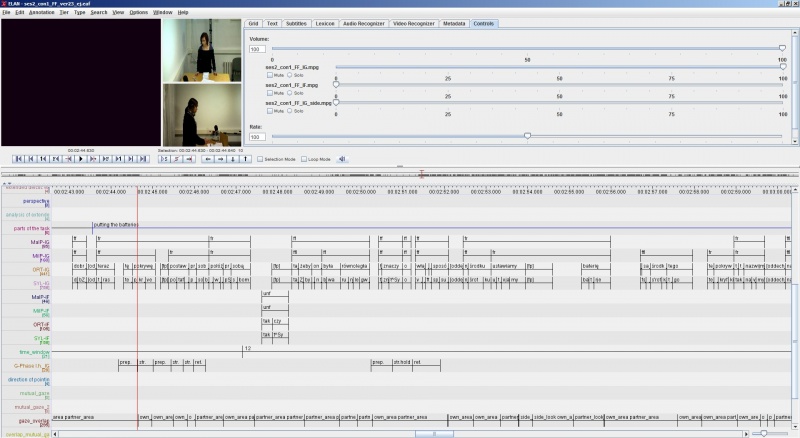

Data description usually is a multi-task process. In case of description of audio data, the tasks include annotation of the recordings, i.e. time-aligned transcription of the utterances so that one can afterwards follow the transcribed text and listen to the recording just like in case of film subtitles. Thanks to this, it is possible to analyse particular speech sounds, syllables, words or any other fragments of the signal (see the animation below). Depending on the needs, annotation can also include other information such as description of prosody, dialogue acts, pausing schemes, hesitation markers, pronunciation errors, individual features of speech or speakers.

A number of computer programs for annotation are currently available and many of them are free of charge for research and education purposes. Some of them enable only annotation of audio files while with others it is also possible to annotate video files (see some of the tools in the list here).

In case when you wish to perform some more detailed phonetic analyses it is useful to choose a tool including a spectrogram to display your sound files (see Chapter 4, especially the section on visible speech). Usually, recordings are first transcribed orthographically (using the official alphabet of the language if it exists) then, phonetically. The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) [21] enables a detailed phonetic transcription of speech. For the needs of computer processing, the Computer Readable Phonetic Alphabet (SAMPA) [22] is also used. Among others, SAMPA owes its popularity to the fact that it does not use any special fonts apart from those available in a standard Latin computer keyboard. For large languages you can find tools to automatize the annotation and transcription work (e.g. GTP – grapheme-to-phoneme converters automatically transforming orthographic texts to phonetic transcriptions, ASR – automatic speech recognition tools). Finding similar tools for endangered languages is more difficult although not completely impossible (see Chapter 4, the section on: Less widely used languages and technology).

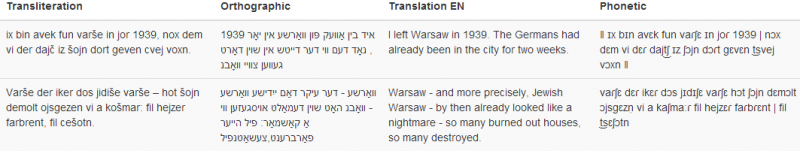

Although phonetic alphabets are most suitable for transcribing speech, it is worth noting that in certain cases it might be preferable to use transliteration (writing the text in one alphabet with the use of another alphabet, e.g. Cyrillic script with Latin letters) or a kind of quasi-phonetic transcription which might lack certain details but on the other hand, is easier for non-specialists. Such solutions are often chosen for corpora or dictionaries dedicated for the use of both scientists and for local communities.

An example record from the Polish Heritage Database: transliteration, orthographic script, English translation, and phonetic transcription for a text in Polish Yiddish (find more at: inne-jezyki.amu.edu.pl/)

Example on-line archives for endangered languages

One of the most important archives for endangered languages is the DOBES (Dokumentation Bedrohter Sprachen) archive dobes.mpi.nl/ – an Internet database of complex documentation for many endangered languages. DOBES is maintained within the Language Archive (TLA) located at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen. This initiative involves not only archiving data and metadata related to endangered languages but also development of linguistic archiving and tools, as well as methods of documentation. Another example of a noteworthy archive for endangered languages is the ELAR [23] at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies, London), also specialising in preserving and publishing endangered language documentation. Apart from providing information and data, both of these archives offer the possibility of depositing and storing your own data on their servers.

The rules concerning the access to data in language repositories are often defined individually for each resource. Some data is publicly available for anyone while for others various limitations may apply. For instance, with some data, you will be asked to contact its authors or contributors in order to get permission, and in other cases you may have to explain the purpose for which you want to use the data before you get permission to download. This might seem complicated but it becomes understandable when we treat the data more as pieces of someone’s real life or heritage than only as “words or sentences” needed for our studies, as was discussed above.

TASK

DOBES is a program that has financed many language documentation projects since 2000. Find a list of these projects here: dobes.mpi.nl/projects. Choose three of the projects and try to answer the following questions:

- What were the main aims of the project? Which researchers besides linguists were involved in the documentation or could be interested in the data?

- How were members of the community involved in the project?

- What kind of data was collected? How was it collected, processed and stored?

An interesting example of a website dedicated to language diversity and endangered languages, including support for indigenous people, where you can also learn about collecting, digitizing and describing data is the SOROSORO program’s website

[24]. The goals of informing and sharing knowledge about endangered languages around the world are also pursued by the Endangered Languages project [25]. An example localised for the region of Poland and the neighbouring countries is the Linguistic Heritage website [6] developed for endangered languages spoken in the territory of central-eastern Europe, once belonging to the so called Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczypospolita), currently being the areas of several countries (Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, and Ukraine). The website was created for the use of both researchers and native speakers of the languages or any other interested persons.

A DATABASE SEARCH TASK

Visit a language database site on the Internet and search it for information about an endangered language(s) spoken presently or in the past in your region of the world.

Pay attention to the types of information provided (descriptions of speakers, culture, geography, sound or text resources in the language).

- You can try out one of the websites:dobes.mpi.nl/projects, www.endangeredlanguages.com, www.sorosoro.org/, inne-jezyki.amu.edu.pl

- Was the search task easy? What kind of problems (if any) can you see?

- Maybe you can find other similar websites?

Legal and ethical problems

One of the main restrictions of using and sharing linguistic resources may be related to the protection of private data. Other restrictions might be a result of cultural, ethical, social or religious issues specific to the linguistic community. Another consideration is that in order to use the data and especially to publish it, it is usually necessary to obtain formal consent from the speakers recorded.

From the legal point of view, the written consent of each participant of a conversation is usually sufficient for recordings. However, legal solutions may vary between countries. For example, recording telephone conversations (even one’s own) without explicit agreement of all participants is illegal in many countries (e.g. Poland, Germany), while some countries allow recording with the consent of only one party (selected states in the USA) or even do not provide any regulations in this respect and thus any recordings of this type are allowed (Latvia).

EXERCISE

Search the Internet and try to find answers that are true for your country:

- Is it legal to record your own telephone conversation with another person?

- Is it legal to use (e.g. as a proof in court) a recording of your own telephone conversation with another person?

- What are the restrictions (if any)?

In practice, speakers are asked to give separate consent to the participation in the recordings, the use of the recording for particular purposes, and last but not least – the publication of the recordings. Most frequently, the consent is prepared in a written form (in case of audio recordings it may also be expressed verbally and recorded together with the remaining data).

| TIP Audio/video recording consent The text of the consent should be clear, free from specialized terminology. Write the text in a way that by signing it the participant:

can give separate consent for:

Consider creating 2 copies of the consent form for yourself and for the participant. |

In the cases of certain local communities, the audio/video recording consent might be not only an individual decision but more a question of the general ‘policy’, customs or attitudes in the community. The documenters need to carefully consider maintaining good relations with the members of local communities, both during the design stage, the proper recordings, and afterwards, when the data are analysed, systematized and processed. The same affects the choice of archiving methods and the ways of sharing the data.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Imagine that you have learned about an endangered local dialect and you would like to become involved in documenting the dialect and/or its revitalisation. What would be your first steps?

First think of your answers and then go to section What can you do – Become a linguist and see working examples of young people doing documentary work.

The interested reader can read more about data, corpora and databases in Appendix 2 to this chapter. You will find there some details about data formats and structures, sharing and exchanging information, plus some more examples concerning the design and development of language resources.

Appendices: More about the history of sound recording, data formats and structures

To find out more about issues related to language documentation see two appendices to this chapter:

- Appendix 1: History of speech recording, reproduction and storage: selected facts. Read more HERE

- Appendix 2: Data formats and structures. Read more HERE

Let’s Revise! – Chapter 10

Go to the Let’s Revise section to see what you can learn from this chapter or test how much you have already learnt!

References

[1] Seifart, F. (2011). Competing motivations for documenting endangered languages. In Haig, G.L.J., Nau, N., Schnell, S., Wegener, C. (Eds.) Documenting endangered languages. Trends in Linguistics, De Gruyter Mouton.

[2] The Linguists: www.pbs.org/thelinguists

[3] Himmelmann, N. P. (1998). Documentary and descriptive linguistics. Linguistics 36:161-195.

(on-line e.g.: http://ifl.phil-fak.uni-koeln.de/fileadmin/linguistik/asw/pdf/Publis/1998a.pdf)

[4] Himmelmann, N. P. (2006). Language documentation: What is it and what is it good for? In Essentials of Language Documentation, Gippert, J., Himmelmann, N. P., Mosel, U. (Eds.), Trends in Linguistics, Studies and Monographs 178:1-30. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin – New York.

[5] Lüpke, F. (2010). Research methods in language documentation. Language Documentation and Description, 7, 55-104.

[6] Poland’s Linguistic Heritage website: inne-jezyki.amu.edu.pl

[6b] Poland’s Linguistic Heritage website (Halcnovian recording): inne-jezyki.amu.edu.pl/Frontend/TextSource/Details/40

[7] Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 209.

[8] Kiel Corpus of spoken language http://www.isfas.uni-kiel.de/de/linguistik/forschung/das_kiel_korpus

[9] Campbell, N. (2002). The recording of emotional speech: JST/CREST database research. Proceedings of Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC), Las Palmas, Spain.

[10] Himmelmann, N. P. (2012). Linguistic Data Types and the Interface between Language Documentation and Description. In Language Documentation & Conservation Vol. 6 (2012), pp. 187-207.

[11] Story Builder: http://www.story-builder.ca/

[12] http://fieldmanuals.mpi.nl/

[13] Bowerman, M., Pederson, E. (1992). Topological relations picture series. In Stephen C. Levinson (ed.), Space stimuli kit 1.2: November 1992, 51. Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics.

[14] The Pear Story: http://www.pearstories.org/docu/ThePearStories.htm

[15] Klessa, K., Wagner, A., Oleśkowicz-Popiel, M., Karpiński, M. (2013). “Paralingua – a new speech corpus for the studies of paralinguistic features”, in Vargas-Sierra, Ch. (Ed), Corpus Resources for Descriptive and Applied Studies. Current Challenges and Future Directions, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Science 95. (48-58), 2013.

[16] IPA Handbook: https://www.langsci.ucl.ac.uk/ipa/handbook.html

[17] Russian Old Believers: http://www.alaska.org/detail/russian-old-believer-communities

[18] DOBES Project: http://dobes.mpi.nl/

[19] DOBES – Deposit your data section: http://dobes.mpi.nl/deposit-your-data/

[20] Gibbon, D., Moore, R., & Winski, R. (Eds.). (1997). Handbook of standards and resources for spoken language systems. Walter de Gruyter. Available on-line at: http://sldr.org/SLDR_data/Disk0/preview/000836/?lang=en

[21] IPA Chart: http://www.langsci.ucl.ac.uk/ipa/ipachart.html

[22] SAMPA Alphabet: http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/sampa/

[23] The Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS, London http://elar.soas.ac.uk/

[24] The SOROSORO program’s website http://www.sorosoro.org/

[25] Endangered Languages website: http://www.endangeredlanguages.com/

Useful links

About language documentation:

- DOBES (Dokumentation Bedrohter Sprachen) – http://dobes.mpi.nl/

- L&C Field Manuals and Stimulus Materials – http://fieldmanuals.mpi.nl/

- SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) – http://www.soas.ac.uk/

- Endangered Languages – http://www.endangeredlanguages.com/

- Endangered Languages Documentation Programme (ELDP) – http://www.hrelp.org/

- SOROSORO – http://www.sorosoro.org/

- Poland’s Linguistic Heritage – http://inne-jezyki.amu.edu.pl

Speech annotation tools:

– for annotation of audio and video files:

- Elan – http://tla.mpi.nl/tools/tla-tools/elan/

- Anvil – http://www.anvil-software.org/

– for annotation and phonetic analysis of audio files (include spectrograms):

- Praat – http://www.praat.org/

- Wavesurfer – http://sourceforge.net/projects/wavesurfer/

- Annotation Pro – http://annotationpro.org/