Book of Knowledge

Chapters: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

List of all languages referred to in the Book of Knowledge and other sections of the website.

DOWNLOAD and print out the Book of Knowledge.

Let’s Revise! – Chapter 9

Go to the Let’s Revise section to see what you can learn from this chapter or test how much you have already learnt!

Chapter author: Tomasz Wicherkiewicz

Introduction

Ethnicity and language

Language policy

Language planning

Language planning in practice

Language revitalization and language maintenance

Notes

References & further reading

Introduction

The native language spoken by a certain community serves predominantly as their internal means of communication (thus, the function used is communicative).

An equally important and salient function of the language is referred to as symbolic. A group of people identify as an ethnic community (ethnos) mainly because they speak the same language (variety), while other/neighbouring communities speak ‘otherwise’ (i.e. use other language varieties = ethnolects). The term ethnos/ethnic community is used here in reference to nations, nationalities, national or ethnic minorities, micronation(alitie)s etc.

Ethnolects spoken by such neighbouring/distinctive communities can be genetically unrelated or distant relatives – in such case they are unambiguously called languages. Frequently, however, they constitute closely related (similar) language varieties, therefore their status as language or dialect (language complex, dialect cluster, etc.) is disputed both inside and outside the community. The status is often determined by means of politics and language policy.

Ethnicity and language

Ethnicity is a term that denotes a subjective sense of community, meaning a shared identity based on common descent which results in a sense of group solidarity. Very often it is regarded by parts of the given community as an objective criterion. The term ‘ethnicity’ derives from the Greek éthnos which originally meant a large, relatively homogeneous group of warriors or a group of animals.

This ethnic sense of community is based on many factors, among which the following are considered the most important:

- the aforementioned and crucial sense of common descent, i.e. common lineage

- language, more appropriately the ethnolect – this is a term in use by linguists (such as Joshua Fishman and Alfred F. Majewicz) to denote a linguistic variety employed by an ethnic group, seen as a vernacular as well as constituting an indicator of the group’s separate identity. In linguistic classification it can correspond to such varieties as: subdialect, dialect, a group of dialects, language and L-Complex (Majewicz 1989: 10-11). The term ethnolect often provides the possibility to avoid (fruitless) debates on whether a given linguistic variety (which can be identified as separate by the ethnic group) is a language or a dialect;

- a similar and subjectively common culture: both spiritual (immaterial) and material;

- Geographical location and the territorial continuity associated with it. Also references to such territories once owned in the past;

- The sense of distinctiveness from other groups (of this kind) as a means of group integration.

Being subjective and instrumental (by means of, e.g. politicians, sovereigns/leaders, the group itself or other groups), the nature of many of these factors contributes to the fact that many scholars on ethnicity more and more often are describing ethnicity and the ethnic group with the term constructed identity. Although language is usually considered as one of the most unequivocal determinants of ethnicity, the criterion of language – as well as the remaining criteria – is often employed in order to construct ethnicity. Thus, the aim of linguistic distinctiveness is to substantiate ethnic distinctiveness, and vice versa: ethnic identity is supposed to substantiate the autonomous nature of the linguistic variety used by the community.

This can be exemplified by the recent, on-going debate in Poland on the status of Silesians and their Silesian language. The distinctiveness of the Silesian language acts as a basis for their separate ethnic identity, while the ethnic identity in question is to serve leveraging the status of the Silesian ethnolect.

Follow this link to find the web portal which controls and coordinates the standardization processes concerning the Silesian language: http://www.ponaszymu.eu.

The discussions on the ethnic status of the Silesian people can be illustrated by the covers of books written by both sceptics and supporters of the idea.

The case of Wallonia represents an example of a different kind of relation between the ethnic and linguistic processes concerning identity. Wallonia is the southern part of Belgium which has gained broad autonomy due to the long standing efforts of the Flemish-speaking inhabitants of North Belgium. Such autonomy was gained along with Flanders, the region of Brussels, and the German-speaking region of Eupen-Malmedy (East Cantons) in East Belgium. The ethnopolitical processes of decentralization and the creation of autonomous regions in Belgium has led Wallonia to seek and develop its own distinct identity; and even to postulate the recognition of its ‘Walloon’ languages (apart from Walloon per se, also the Picard, Lorrain and Champenois ethnolects) as being an L-complex which is distinct from the French language. This L-complex would be a mark of Walloon ethnicity – separate from both the Flemish-speaking and German-speaking Belgian people, and from the French or the immigrant French-speaking populace of Belgium. Below you can see two editions of The Little Prince (Le Petit Prince) translated into Walloon and Picard.

Generally, making use of the mutual relationship between ethnicity and language/ethnolect results from the political aspirations of certain groups and/or their leaders. Often they hold expectations and require linguists to fulfil them by providing conclusive evidence on whether the linguistic variety in question is a fully-developed language or a mere dialect of another (national and official!) language. This matter cannot be resolved, however, by considering only the intralinguistic features (the lexical and grammatical systems) of language. It is the extralinguistic criteria that determine the high or low linguistic status of a variety: its geopolitical, military and historical background. This is best described by the well-known metaphor attributed to the Yiddishist Max Weinreich: ‘a language is a dialect with an army and navy’.

Language does not constitute the sole determinant of ethnicity – this can be supported by examining examples of different ethnicity that are based on the same language or its similar varieties. For example, the ethnicity of Dutch people in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and of Flemish people in the Kingdom of Belgium; the ethnicity of Croats, Serbs, Bosnians, and the Montenegrins; the ethnicity of the British, USA Americans, Australians, New Zealanders and many others.

It is, thus, impossible to assign a separate language/ethnolect to every existing ethnic group – and vice versa. It is an even more daunting task with regards to national states. This means, as was said previously, that leaders/politicians and groups of interest will strive to raise the status and prestige of their own language variety in order to underline and emphasize their ethnicity and the distinctiveness from other ethnic groups they already possess. Opposite phenomenon/processes may occur as well: based on the differences between linguistic varieties, the group will want to create and strengthen their ethnic separateness. Many of such linguistic varieties are endangered in today’s world. Raising their status and prestige may reduce this endangerment and/or halt the process of language death, at least according to the groups employing the given variety. Another notion that reflects the subjective nature of the bonds binding communities into ethnic groups is the notion of the imagined community. This term was coined by Benedict Anderson and introduced in the title of his book reissued in 1991. The notion can be most easily explained by understanding an ethnic group (or a nation in a broader context) as a community which has been socially constructed through means of a subjective belief of its members that they are, indeed, members of the said community. Yet again this can be exemplified by processes which develop ethnicity without the role of language as the decisive factor, as well as processes which construct ethnic identity hand in hand with language separateness.

The Hui people can act as an example of the first process. The Hui people are a community of nearly 10-million Chinese Muslims who are recognized by Chinese law and by the Chinese government as an ethnic minority. They, however, do not have their own language that could act as a distinguisher. Arabic, used in the whole of the Muslim world as a liturgical language, cannot be treated as such – it is not used as means of communication neither by the Hui people nor by many other peoples practicing Islam. The legal recognition as an autonomous ethnic group and, on top of that, the granting of the autonomous region of Ningxia in North China strengthened the ethnic identity of the Hui people. They can be, thus, treated as an example of an ethno-confessional identity (one based on religious separateness).

Follow this link to a video clip regarding the Hui people’s identity. Pay attention to the standardized form of Chinese that the characters are using: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DOwgqGVgfgQ.

In the chapter devoted to writing systems (Chapter 5) the case of the Dungan people is discussed. The Dungan people are a community deriving their origin from the Hui people who settled in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Given the diaspora, their language became autonomous – and their ethno-confessional identity developed into an ethnic one.

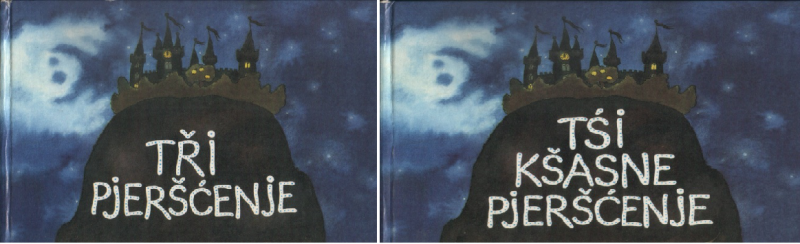

These linguistic and ethnic processes are employed also in the formation of collective identity of, for example, the Rusyns. The Rusyns are communities that use East Slavic language varieties in Central Europe, that live or lived in the Carpathian mountain range and, also, that adhere to the traditions of Eastern Christianity (and, thus, use the Cyrillic script – see Chapter 5 on Writing Systems). The Rusyn L-complex (often and by many treated as a group of dialects of Ukrainian) comprises of the following varieties: Lemko in Poland, Pryashiv Rusyn in Slovakia, Subcarpathian Rusyn in Ukraine, Pannonian Rusyn in North Hungary, Rusyn in Vojvodina (an autonomous province in Serbia), and also, according to some, the Boyko varieties in Poland and Ukraine, and Hutsul in Ukraine. The first Rusyn variety that created its own official literal standard form was Vojvodinan Rusyn – it was even one of the official languages there. It all happened in the times of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Below can be found a photograph taken in Novi Sad (capitol of Vojvodina) showing a sign meaning “bus station” in: Serbian, Croatian (the first and second signs are at the same time the Cyrillic and Latin versions of the Serbo-Croatian language), Hungarian, Slovakian, Romanian and Rusyn.

Although the Rusyn standard was well established in the Yugoslav Vojvodina, it cannot be treated as the norm of a common Rusyn language as it contained too many West and South Slavic features. Apart from that, the political status of Rusyns was different depending on the country they lived in. The recognition of Rusyns as a separate ethnos/nation took different amounts of time – in Ukraine it was only 2012 that a bill had been put forward that granted regional language rights to minority languages, Rusyn among them. The creation of a standardized form of the Rusyn L-complex is, thus, a matter of time – similar to the formation of a common Rusyn ethnic identity.

Follow this link to find a performance of the Rusyn ‘national’ anthem – such symbols (as anthems, flags), too, constitute essential factors in the process of forming an ethnic identity: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBh6BKgWugk.

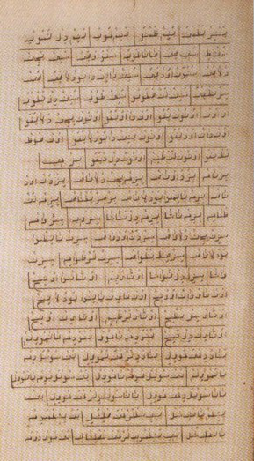

Yet another illustrative example of the transfer from a clearly religious identity to an ethnic (or ethno-confessional) identity and, then, a linguistic one is the case of Lipko Tatars (also known as Polish-Lithuanian-Belarusian Tatars and Tatars of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania; not to be mistaken for, e.g. Crimean Tatars or Volga Tatars). Deriving from different tribes of the Golden Horde, Tatars started settling in, or were resettled to, Lithuania by the XIV century and in Poland by the XVII century. Their descendants relatively quickly abandoned the Tatar language and formed their identity based on the traditions of Islam, although under heavy influence of local Christian traditions. The Arabic script was a source of Muslim values and was even employed by the Polish-Lithuanian Tatars to record the local Polish-Belarusian varieties. Below can be found a page from an Arabic-Polish dictionary which was a part of a kitab – a kind of a hand-written book preserved to this day by many Tatar families.

The Polish-Lithuanian Tatars for over three centuries functioned as an ethno-confessional community lacking a vernacular ethnic language. It was most probably due to the European revitalization movements that they decided upon stepping on the path of ‘revitalizing’ their own language – in their own understanding of the term. On the official website of the Tatar Union of the Republic of Poland (Związek Tatarów Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej: http://www.ztrp.org/index.php/tatar-tele.html) one can find basic information about the Volga Tatar language and its (Cyrillic) alphabet, along with exercises. It is around the Volga variety that the Polish Tatars want to construct their ethnicity – with no connection to past times, thus giving them a fresh start.

| The intensification of ethnic movements around the world was most noticeable by the end of the 20th century. Since then, they have been accompanied by endeavours to raise the status of many linguistic varieties. In many cases these ethnopolitical movements aim to counter the European ideology behind language that pervades the world, and break up with the synonymy of: |

| Nation=state=language |

Introduced after the French Revolution, this notion constitutes the building block of many countries over the last two hundred years, especially of the 20th century. It still is believed to be an acceptable model of how a (national) state should function along with its (national) language. This simplified correspondence can, however, be easily countered by comparing the number of countries in the world with but an approximant number of ethnic groups and the number of languages discussed in other chapters of this publication. The policies of many countries aim at ethnic homogeneity – that is, making the whole of a population of a country uniform and attributing them with a feeling of being a part of an indivisible nation. Languages may become ‘victims’ of such ethnic homogeneity policy; especially language that do not enjoy the political status and social acceptance of being national languages. These officially unrecognized minority groups have answered to this by launching numerous ethno-linguistic movements in the 20th and 21st centuries that strive to grant these minorities legal rights in different domains:

- the recognition as an ethnic minority – as in the case of the Rusyn people,

- the granting of a special territorial status – as in the case of the Kashubian language in the Pomerania region of Poland,

- the granting of politico-territorial autonomy – as in the case of the autonomy of Silesia,

- the recognition of the language variety as a separate language (raising its linguistic status),

- the recognition as an auxiliary language, second language, or an equal co-official language on a given territory.

As has been repeatedly emphasized in this chapter, the vast majority of the world’s countries are multi-ethnic societies, which trait in turn is connected with their multilingual character. Among them one can list: Papua New Guinea and the Republic of Indonesia (it comes as no surprise that the island New Guinea, with around a thousand languages being spoken there, belongs to both of these countries); the island countries of the Republic of Vanuatu and the Salomon Islands in Oceania; the Republic of India, the People’s Republic of China, Malaysia, Nepal, Myanmar (Burma), the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in Asia; the Republic of Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Chad and the Republic of Tanzania in Africa; also the United States of America and the Russian Federation.

Listing monolingual and, thus, mono-ethnic countries causes much more difficulty. These can be, for example: The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea (both considered being the most homogenous countries in the world). Countries that are almost fully homogenous with respect to language and ethnicity can be listed the following way: the Caribbean Republic of Haiti, the Republic of Cuba, the island state of St. Vincent and the Grenadines (the indigenous Indian populace has left the island by the most part), the Republic of Salvador in Central America, the Independent State of Samoa in Oceania, also the Republic of Rwanda and the Republic of Burundi in Africa, as well as the Republic of Maldives in the Indian Ocean. The Vatican passes as the most monolingual country in the world (even though legally it has two official languages: Italian and Latin. The second language is not even used on the country’s official website www.vaticanstate.va. It is worth mentioning that only the official status of the two languages is being discussed here; in reality, citizens of Vatican are multilingual due to the multinational nature of the Catholic clergy, administrative officers and service staff. A ‘Vatican ethnic identity” hardly exists at all).

Language policy

One of the definitions of language policy describes it as a set of any legislative acts that strive to shape the relations between society and the language or languages that exist and are used in this society (if at least symbolically) (Kaplan & Baldauf 1997: 12). Language policy is concerned with:

- the official language or languages (known also as state or national languages) that function either de iure (through legislative proceedings as French in France or Polish in Poland) or de facto (in practice as in English in the United Kingdom or the United States)

- regional languages

- (ethnic/national) minority languages

- sign languages (used by the deaf, deaf-mute and hard-of-hearing communities)

- immigrant languages

- foreign languages that are taught and spoken

- classical/dead languages existing in the education system and certain occupations (for example, Latin in medicine) or used in religious context (for example, Latin, Ancient Greek, Old Church Slavonic, Biblical Hebrew, Quranic Hebrew, Sanskrit, and the classical Grabar language of Armenia, and others).

In many countries and especially in Europe, the term regional language denotes an autochthonous (i.e. indigenous) language which is not a language of an ethnic minority (that is, its speakers do not feel ethnically/nationally separate from the majority of the society) and which is closely related to the major (official) language of the given country. It is so to the point of naming it a dialect of the national language, even though in many cases historically it developed not as a variety (as a dialect) but in parallel. Among such languages one might list Kashubian or Silesian in Poland, Low German in Germany and the Netherlands, Scots in Scotland/Northern Ireland, Asturian in Spain, Latgalian in Latvia, Samogitian in Lithuania, and Võro and Seto in Estonia.

Recently sign language has begun to be treated similarly to languages of ethnic minorities – mostly by sociolinguists but, in some countries (for example Finland), also by their governing bodies.

Usually, language policy constitutes an element or one of the areas of a country’s ethnic and cultural policy. Apart from making decisions that regulate the relations between different ethnic groups in a country, the state may also take action in order to either support a given language or language variety, or quite the opposite; it may discourage their use or even ban the varieties in certain or all domains of language use. As a whole, these decisions and actions can be described as language planning. In extreme cases they can be called language engineering – a phenomenon which can be exemplified by the language policies of Lenin and Stalin in Soviet Russia, which were taken as an example in the People’s Republic of China with regards to its ethnic minorities. The aim of its endeavours was not only to regulate the relations between ethnic and language groups in the country but also to manipulate the groups through their creation, merging, separation, transformation or removal. This was done by means of nomenclature, border change, ethnic propaganda and, of course, language policy.

Throughout human history the actions of different language policies have taken the shape of the persecution of one ethnic group and/or granting privileges to another. These actions can include assimilating whole groups or individuals into the major ethnolinguistic group, depriving the groups of the possibility to express their group ideals and values, relocating them due to their ethnicity, introducing inner colonialism (assuming that a certain group inhabiting one’s country is inferior and treating it as such), or even, in extreme cases, committing ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Less violent examples of unequal language policy include stereotypization, i.e. the forming and spreading of bias towards one’s ethnicity, nationality, race or religion, and ubiquitous ethnocentrism, i.e. considering one’s own ethnic group as the privileged one and concentrating the efforts of ethnic policy on supporting it. An ethnic policy that supports different or all other ethnic groups inhabiting a given country encompasses, for one, the equal or, at least, similar consideration for every element forming an ethnic identity of a minority or a majority group. Also, it should provide minority groups the right of participation in making political decisions as well as it should ensure the equality of the rights of minorities with the rights of the majority. In the context of minorities which are threatened with extinction or full assimilation, language policy ought to take steps towards employing positive discrimination/ affirmative action (enforcing auxiliary laws that apply only to the given group in order to ensure their survival) and giving legal and political guarantees concerning the support and protection of minorities both on a national and international level.

Language planning

comprises any decision or action made by the government, or different organizations, institutions, groups or individuals which are to affect the presence, use and development of a language or languages.

These decisions are made to answer the demands of society and politics, when, for example, different groups of speakers of different languages or language varieties strive to ensure the unhindered and day-to-day presence of their languages in various domains, or when some of these domains are unavailable to certain (often minority) groups. State institutions and NGOs are faced, thus, with the necessity/need to fulfill these linguistic needs, which are voiced by either the majority of the society (in which case it often concerns the linguistic uniformity of the whole country) or by minority groups (who often are in favour of a country being as multilingual as possible), and to fulfill them effectively and justly. In multilingual states/societies the ideal scenario consists of a situation in which state institutions and governmental bodies and their service are available at a similar level to users of different vernacular language varieties. In reality, however, the aim of language planning is to limit linguistic diversity by appointing a single, official language in a multilingual state or, for example, by ascribing the status of a “standard” language to one of the used varieties in order to promote linguistic uniformity. The first type of action plan may be exemplified by the language policy of the Republic of Indonesia, one of the most multilingual regions in the world. Across all of its territories and domains of public life, it actively supports the use of a unified Indonesian language Bahasa Indonesia. The second action plan can be represented by the People’s Republic of China which strives to consolidate the country and nation by means of encouraging the use of the Mandarin Putonghua, but one of the many linguistic varieties that exist in China.

Language planning in practice

Languages, especially endangered ones, very often require decisive and informed language planning campaigns in the following areas:

- education, e.g. specialized curricula concerning the teaching of a language and the teaching in a language

- normalization and standardization of endangered languages

- support for endangered language’s publishing industry

- the legislative conditions concerning language

- raising the prestige and status of a given language in public life

- promoting bilingualism in trade and in the workplace

- promoting bilingualism in administration and society

- encouraging the increase of the presence of a language in the (local) linguistic landscape.

Initiatives taken up as a part of language planning may concern various areas of language use and language presence:

-

corpus planning – meaning the standardization of language and its normalization (see below); the choice of one particular language variety over another to become considered the basic form, whether acting as an official language or literary language; the publishing of language guides, dictionaries, normative grammars, handbooks of orthography; the creation of research circles or associations (concerning literary studies or linguistics), publishing handbooks, and also organizing spelling competitions;

-

status planning – is concerned with granting status, for example, an official, co-official, working or auxiliary status to a language on a national or regional level, especially in domains of education, administration, service, trade or media; sometimes also in the areas of regional legislature, justice system and relations with other groups. Status planning also applies to prohibitions imposed on certain areas of language use;

-

acquisition planning – it encompasses all initiatives (legal instruments and normative acts included) that regulate the teaching of a language in the domain of education (teaching through a language, teaching as a national language, teaching as a foreign language, pre-school and adult courses, external courses) and language competitions that promote learning;

-

language technology planning – often considered the newest dimension of language planning. It creates the possibility of language use in text editors, on-line dictionaries, cell phones, cash machines, etc.

Language planning, as understood from the above listed aspects, should be employed in a number of stages. The first stage usually is the analysis of linguistic behaviour in society (or a smaller community) that uses a certain language or a whole range of languages (like the previously mentioned official, regional, minority, community, taught, and foreign languages). The next stage is to choose which language variety will be liable for language planning and its following aims:

codification – the provision of criteria or features of a “correct” language variety,

standardization – the establishment of a uniform version of the language, the development of vocabulary and a variety of languages styles allowing the language to function in a broad array of domains,

normalization – the development and expanding of the aforementioned areas of language use. An example of this comes from Catalonia. For the past thirty years, the regional government of Catalonia has put in place policies and other initiatives to encourage Catalan speakers (both fluent and potential) to use the language in all domains possible and make Catalan the “default” language of communication. Click here to see some examples of posters produced, which help speakers make sure they know the correct term in Catalan for a wide range of subjects.

language cultivation – the establishment of language councils and academies, the encouragement to use the language and its codified variety.

The ultimate aim of language planning, thus, is to maintain the presence of a language in each domain of public life in which the language has the capacity to function. Another primary aim of language planning is to create the best possible environment for broad language development, even though at the turn of the 21st century most of the languages of the world have been deprived of such environments.

Language revitalization and language maintenance

In sociolinguistic and language ecology terms, strategies and actions that focus on the restoration of (at least some) functions and areas of usage to endangered languages are known as language REVITALIZATION, REVIVAL and RECLAMATION. These strategies and actions usually occur after a certain period of limited or completely abandoned use of such languages. The term language MAINTENANCE, on the other hand, is employed to describe such strategies and actions that support and strengthen an endangered language that still functions and which is spoken by young users (the youngest generation still learns the language), though its use is growing weaker.

In popular terms, language maintenance, revival and revitalization are often used interchangeably to describe different linguistic situations. Strictly speaking, though, the terms refer to different processes in linguistic management. In case of the official languages, language maintenance occurs when some official body makes provision for the inclusion of new loanwords from other languages, as happens with the Académie Française in France, for example. It also refers to legislation which makes a language official – for example, when the majority of American states declared English as the official language (variously, between 1812 and 2008; see here for details), the aim was to maintain or enforce the dominance of English in these states. Language revitalization concerns the strengthening of a language that has suffered loss in the number of speakers. Evidence from placenames shows that Basque was once spoken much further eastward in the Iberian peninsula that it currently is, indicating that the language has been receding over the centuries (see the animated picture on the right for a visual representation of this shift)

However, the number of Basque speakers is in fact increasing – according to official statistics, there were 528,500 speakers of Basque in 1991, 665,800 speakers in 2006 and 714,136 speakers in 2011 (Gobierno Vasco 2012). This is largely due to revitalization efforts in the schools.

Language revival refers to a language which lost all of its speakers and has been reconstructed at some point after the last speaker died. Cornish was used as a community language in Cornwall, United Kingdom, until the late 18th century. A limited number of people did continue to use the language throughout the 19th and possibly the early 20th centuries. Literature from the Medieval and Tudor periods, and substantial fragments, including grammars, from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries survived, which allowed Cornish to be revived in the early 20th century. However, the revival led to six forms of ‘revived Cornish’, with many disputes arising over which form was most ‘authentic’. In 2008 a ‘Standard Written Form’ was agreed upon by most users of Cornish (Cornish Language Partnership), whether this has settled all the disputes remains to be seen (a review was due in 2013). Thus language revival often results in language transformation as much as anything else, as reproducing the speech of speakers from the past is nigh-on impossible.

Language revitalization has two main aims:

-

Teaching the language to those who do not speak it – this is fulfilled through different kinds of educational campaigns, that is actions within the scope of language acquisition planning. This subject will be discussed further on when examples of teaching endangered languages will be presented;

-

Encouraging both learners and fluent speakers of a language to use it – in a more and more varied range of situations and areas of usage. Organizations, institutions and unofficial groups often take up campaigns to promote this notion. These kind of initiatives are carried out often in a form of posters that promote extensive and frequent language use. See below the posters concerning Frisian (Praat mar frysk [1]– which translates as “Just speak Frisian!”), Kashubian (Ma tiż rozmiejemë gadac pò kaszëbskù – “Here we speak Kashubian, too!”) which are placed in trade and service offices and encourage to use Kashubian out of home). Another example is a flyer prompting to take part in a competition – Plattdütsk bi d’Arbeid – besünners för jung Lü (‘Low German in the working place – especially for the young”). [2]

* * *

Leanne Hinton (2011: 292-293) enumerated a set of actions corresponding to the possibility of revitalizing/reclaiming an endangered language or a “sleeping” language (that which has no native speakers – one can only try to revive this kind of language). These actions include:

- Teaching a number of words/phrases such as greetings, short conversations and expressions allowing for establishing contact with others;

- Gathering publications in and about the endangered language, preparing notes and recordings in order to create an archive of the language;

- Creating/correcting writing systems, creating dictionaries (also illustrated dictionaries for children) as well as practical grammars and course books (also alphabet books) for language learning;

- Recording audio- and/or audiovisual materials of the living speakers of the language in order to create linguistically varied corpora so that examples of language use can be documented;

- Organizing language classes, summer schools and language camps;

- If possible, running community schools in the form of immersion schools for children (see below).

It is the teaching of language, whether in existing or in new educational facilities, that constitutes the most frequently employed tool of language revitalization/language maintenance. There are many ways to teach an endangered language:

- regular language classes within the scope of a school curriculum.

|

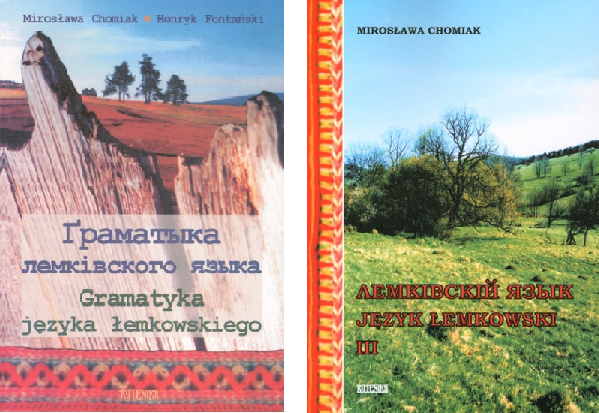

It was not until 2001 that the Lemko language was introduced to a number of schools in Poland. It is the vernacular language of the Lemko people which are acknowledged as an ethnic minority in Poland. In other countries they are known as Rusyns, Ruthenians or Carpatho-Rusyns. According to the General Censuses of 2002 and 2011 the number of people considering themselves Lemkian is about 5000-7000. Almost all of them declared that they use the Lemko language at their homes. The language is endangered mostly due to the assimilation by the Polish-speaking environment and also by the fact that Lemko was identified for many years as a dialect of Ukrainian. Today this language is taught from 1 up to 3 hours per week by 268 children in the whole of Poland: 5(!) children in 4 kindergartens, 110 children in 20 primary schools, 90 students in 10 junior high schools, 20 students in 2 high schools, 1(!) student in 1 vocational school and 42 students in 1 school complex. More information and materials covering the Lemko people and their language can be found on www.lemko.org; you may also listen to the Lemko radio ЛЕМ.fm on www.lem.fm, watch an interview with a Lemko Orthodox priest A. Graban from Strzelce Krajeńskie (Keeping the Lemko language alive – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JXSxAoZiOOk), listen to Lemko songs by the young band Lemko Tower (http://www.youtube.com/user/LEMKOTOWER1), and also read the brochure about the teaching of Lemko (and Ukrainian) in Poland on http://www.mercator-research.eu/fileadmin/mercator/dossiers_pdf/Ukrainian_Ruthenian.pdf. |

- bilingual teaching encompassing the learning of a number of subjects in the endangered language.

The network of bilingual Sorbian-German schools in Upper Lusatia in Saxony, Eastern Germany, may serve as an example. The Sorbs are a small West-Slavic nation who uses two (standard) Sorbian languages: Lower Sorbian and Upper Sorbian.

The Upper Sorbian language is mainly used in the traditionally Catholic part of Saxony and, with around 18.000 people speaking it, is considered endangered (Ethnologue 2009). Lower Sorbian developed in the traditionally Protestant Brandenburg (former Prussia) and is in serious danger of extinction having less than 7.000 users. Bilingual schools provide the teaching of Upper Sorbian; Lower Sorbian is being revitalized via immersion schooling in a network of schools and nursery schools known as Witaj.

The role of education in supporting the Sorbian languages in Germany is described in this brochure: http://www.mercator-research.eu

Another example of this type of education focused on endangered language communities, in particular in lowly populated areas, are boarding schools. Here you can see children from a South-African school which runs, among many other, classes of the revitalized languages of the Khoisan language family.

- bilingual schooling encompassing the teaching of all (or most) subjects in the endangered language – sometimes shifting between teaching in the minority language and in the dominant majority language. The photography below comes from a primary school in Baygamut – one of the two settlements of the Kazakh minority in Russia. The school is attended by less than 20 students and is located in a remote part of the Altai Krai. Despite the abject poverty of the area, due to the eager support of the school’s head office, its teacher and the local education authorities, the Kazakh language, just like Russian, is a fully developed and frequently used language, which is by no means endangered.

– the aforementioned immersion schooling – the language in which teaching is conducted in immersion schools and nursery schools is the endangered language itself. The dominant language of the majority is often taught as a foreign language. An exceptional example of immersion schooling are “language nests” (Spanish “nidos de lengua”) in which the roles of teachers in nursery schools (or the first years of primary education) are taken up by grandparents who are the last fluent speakers of the dying language. Such “language nests” have achieved great success in the revitalization of these languages, among others:

- the Māori language of New Zealand [3] (Te Kōhanga Reo – see http://www.kohanga-reo.co.nz)

- the Hawaiian language of Hawaii[4] (Pūnana Leo – see http://www.ahapunanaleo.org)

- the vernacular languages of Mexico, the Aztec and Mayan languages included (see the video clip on Nido de Lengua de Izamal [5] http://vimeo.com/36603789)

- the Saami languages of the Saami people [6]

- the Lower Sorbian language spoken by Lower Sorbs in Eastern Germany is being revitalized through the functioning of the network of immersion nursery schools and immersion schools Witaj (see: http://www.witaj-sprachzentrum.de; http://www.witaj.de).

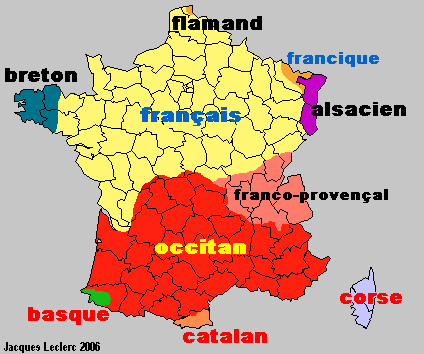

– school networks established on the initiative of the community itself – they were set up in order to teach endangered minority languages on the initiative of parent groups in particular as a reaction to the hostile or indifferent attitudes/policies of state educational authorities. One should mention here the numerous schools for children belonging to the autochthonic language minorities of France. The French Republic’s constitution does not acknowledge the existence of minority languages on its territory, naming them instead langues regionales. The legislation of the educational system does allow, however, for the establishment of such community schools which provide a wide range of minority language teaching methods.

- the Breton Diwan school network (www.diwanbreizh.org) [7]

- the German-language schools ABCM Association –Zweisprachigkeit in Alsace (http://www.abcmzwei.eu/sprachigkeit) [8]

- the Catalan Bressola school network (http://www.bressola.cat) [9]

- the Occitan Calandretas school network (http://calandreta.org) [10]

- the Basque Ikastolak school networks in Spain and France (www.ikastola.net) [11].

– classes organized outside the school system – by institutions, individuals, summer language schools, etc. Wilamowicean, a language used in Wilamowice in southern Poland, may serve as an example of a language which has been revitalized using exclusively extra-institutional methods. The efforts to revitalize the language have been undertaken mostly by Tymoteusz Król, a teenager at the time he began. He runs private language lessons, he is in the process of creating a dictionary and a grammar of the language, archives it through making recordings and notes; he also writes in Wilamowicean, collects Wilamowian folk costumes and popularizes the knowledge about the Wilamowicean language and Wilamowian culture (see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nbJ9fW7WWk). Another example: the teaching of a very endangered language, Karaim. The picture below shows prof. Éva Á. Csató Johanson, originally from Budapest, now working in Uppsala, assisted by a native speaker of Karaim, who are teaching the language to a group of children on a summer language course in Trakai in Lithuania. [12]

[there will be two more video clips here]

So far, examples of the areas of use of a language have been discussed, as well as the areas in which revitalization is possible. Now it is time for the illustration of ways that the presence of a language can be supported in a variety of its areas of use:

- underlining the presence of language in the private linguistic landscape – here is a sign placed in a car transporting little children. The text is in the South Estonian language Võro. Of course apart from cautioning other drivers, it is also a means of manifesting one’s knowledge of the language and the fact of using it even in such a peculiar communicative context, although it is usually used explicitly in home and family situations.

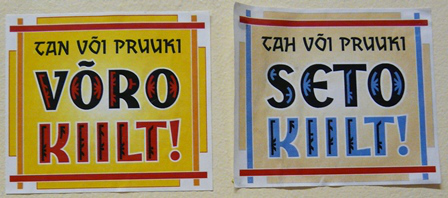

- Underlining the presence and usage of the language in the public linguistic landscape – which can be exemplified by stickers that encourage to use lesser used languages, in this context the two varieties of Southern Estonian – Võro and Seto [13]

- Some endangered minority languages may use institutional support in order to become present not only in the public, sometimes official, linguistic landscape but also to sway the legal authority’s decision. Here is the Saami Parliament in the town of Kurina (which is Giron in Saami) in Lapland Sweden.

|

|

|

| Photo by T. Wicherkiewicz | Photo by T. Wicherkiewicz |

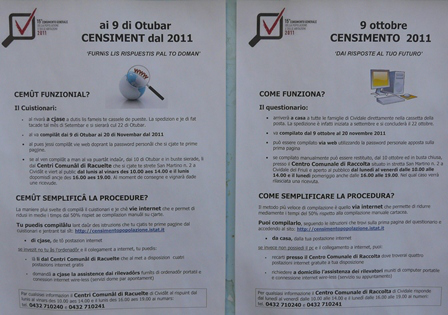

– Another way of supporting an endangered minority language is to promote it even in the most official domains used by the state. Below one can see a bilingual Friulian-Italian poster encouraging to participate in the Italian General Census 2011. [14]

– One of the areas that endangered languages rarely engage in is trade and commerce – it is, however, an area of great importance for the correct functioning of every language. In the photography one can see a shop in the town of Vielha with the name and advertisements in the Aranese language. [15]

– Certainly, preparing and publishing attractive educational materials can serve a great purpose in strengthening a language’s status, especially there where it is taught.

- Popularizing and promoting the presence of an endangered lesser used language in mass culture – here is the South Estonian band Neiokõsõ, which achieved great success in the 2004 edition of the Eurovision music festival. They represented Estonia with their song sung in the Võro language – an action which lead to a great increase in the Estonian society’s interest in this endangered language variety (listen here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8gOwmmxQaho);

- Microlanguages are languages that are spoken by a small group, of a few or of a dozen, last speakers. These languages do, indeed, require a huge range of revitalization efforts, if revitalization is possible at all. That is why these efforts often employ the documentation of the endangered language in writing and recordings as comprehensively as possible, as well as the symbolical combining the language into the linguistic landscape.

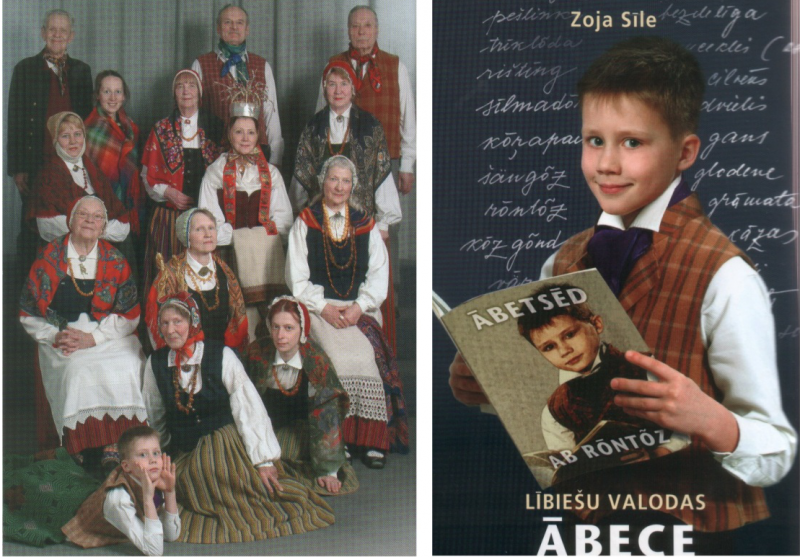

The Livonian or Liv language of Latvia can be included in the category of “sleeping” languages. It is spoken by a handful of last speakers, most of which, if not all, have been framed within the picture below (the boy lying on the floor on the left is also on the cover of the Alphabet Book for learning Livonian). Right next to it see the cover of the newest (and probably last) alphabet book for learning Livonian – the boy on the cover holds an alphabet book published before the II World War when Livonian children were taught their language in schools in north-west Latvia. More information about the Livonian language can be found here:http://www.livones.net.

Notes:

[1] The website www.praatmaarfrysk.nl has been dedicated to this initiative, as well.

[2] More information about these languages (mainly their presence in the education system) can be found in these brochures:

[4] Hawaiian is also an East Polynesian language. It is, however, more seriously endangered than Māori as the number of its speakers spans from 1.000 to 8.000 (Ethnologue 2009) regardless of the fact that there are 240.000 native Hawaiians on Hawaii (around 100.000 more live in other US states). At the beginning of the 20th century, 37.000 people considered Hawaiian their first language.

[5] Izamal is a town in the Mexican Yucatan Peninsula (The Mayan name is Itzmal). A large portion of its inhabitants speak the Mayan language Yucated as their vernacular language. The language is not considered endangered because it is transferred from generation to generation, and the total number of its users (according to Ethnologue 2009) amounts to 700.000. The teaching of this indigenous language is conducted through the system of language nests which is hoped to maintain it.

http://www.cneii.org/documentos/libros/nido-de-lengua-ingles.pdf

[6] Revitalization initiatives (for example, the language nests project) are to halt the rapid death of the Saami languages, especially the extremely endangered Inari Sámi (300 speakers in Finland according to Ethnologue 2009) and Skolt/Koltta Sámi varieties (400 in Finland, 20 in Russia) – see http://www.skr.fi/default.asp?docId=19214

[7] Breton is the only Celtic language that is spoken outside the British Isles, on continental Europe. According to Broudic (2007), it is spoken by about 270,000 people. More about Breton in education can be found in this brochure:

[8] The Alemannic variety of German is still a second language for the majority (1.5 million) of the inhabitants of Alsace, the North-Eastern region of Germany with its capital in Strasbourg. More about the teaching of the German language in the French Alsace can be found in this brochure:

[9] Catalan is an example of a language which is by no means endangered in one country (The Kingdom of Spain in which it has over 11 million speakers along with its Valencian and Balearic varieties) and , at the same time, is threatened with a break in intergenerational transmission and with the shrinking number of domains of usage in another country (The French Republic where Catalan is spoken by around 100,000 users). More about the teaching of Catalan in France can be found in this brochure: http://www.fryske-akademy.nl/fileadmin/mercator/dossiers_pdf/catalan_in_france.pdf

[10]The Occitan language is, actually, a whole L-Comlex encompassing the Southern-French varieties of Provencal, Gascon, Languedocien and Limousin. Despite a vast number of speakers (close to 2 million according to Ethnologie 2009) it is a language threatened with the break of intergenerational language transmission. More about Occitan in French education can be found in this brochure: http://www.mercator-research.eu/fileadmin/mercator/dossiers_pdf/occitan_in_france.pdf

[11] Basque is a non-Indo-European language and, similarly to Catalan, it is almost in no danger in the Kingdom of Spain (where it has over 500,000 speakers) and moderately endangered in the Republic of France (where Basque is spoken by about 75,000 people). More about Basque education in France can be found in this brochure: http://www.mercator-research.eu/fileadmin/mercator/dossiers_pdf/basque_in_france2nd.pdf

[12] The Karaims are the smallest of the officially acknowledged ethnic minorities in Poland (around 50 people) and Lithuania (270 people). The Turkic Karaim language that originated on the Crimean Peninsula is used by around 120 speakers (and an unverifiable number in the Ukrainian part of the Peninsula). The website www.karaimi.org is dedicated to the Karaim people; more about the revitalization of the Karaim language can be found on http://www.hrelp.org/events/workshops/eldp2007_9/resources/multimedia.ppt as well as http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/6083/1/karaim_orthography.pdf

[13] The Võro and Seto varieties are used in the south of Estonia (Seto also on the borderlands in Russia) by, accordingly, 70,000 and 10,000-13.000 people. Despite a separate history of development and a separate linguistic identity from that of Estonians (in the case of Seto, also a separate cultural-religious identity), these languages have no official status in Estonia which is a factor strongly impeding their vitality. Since some time ago, school and extra-school language courses have been organized.

http://www.mercator-research.eu/fileadmin/mercator/dossiers_pdf/voro_in_estonia.pdf

[14] the Friulian language is one the minority languages of Italy; the picture was taken in the small town of Cividale del Friuli (which is Cividât in Friulian). Due to the support of the Italian state, this language is used by nearly 800,000 speakers and is, thus, less endangered than it was in the past. More on Friulian-Italian bilingualism can be found here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rXQOXCGdrRk ; the website of the Friulian Language Society is: http://www.filologicafriulana.it

Let’s Revise! – Chapter 9

Go to the Let’s Revise section to see what you can learn from this chapter or test how much you have already learnt!

References & further reading:

- Anderson, Benedict R. O’G. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London-New York: Verso.

- Coulmas, Florian (red.) 1997. The Handbook of Sociolinguistics. Oxford-Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Drozd, Andrzej, Marek M. Dziekan, Tadeusz Majda 2000. Piśmiennictwo i muhiry Tatarów polsko-litewskich. Warszawa: Res Publica Multiethnica.

- Ethnologue. Languages of the World 2009 (16th edition). Dallas: SIL International.

- Fishman, Joshua A. 2000. Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Clevedon: Multiingual Matters.

- Hinton, Leanne 2011. “Revitalization of endangered languages:, w: Austin, Peter K. & Julia Sallabank (red.) The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge University Press. 291-312.

- Kaplan, R. B. & Baldauf, R. B. 1997. Language Planning: From Practice to Theory.Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Majewicz, Alfred F. 1989. Języki świata i ich klasyfikowanie. Warszawa:Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Cornish Language Partnership. Standard Written Form. http://www.magakernow.org.uk/default.aspx?page=346 (Retrieved 30 November 2012)

- Gobierno Vasco (July 2012). “V. Inkesta Soziolinguistikoa”. Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco. http://www.euskara.euskadi.net/r59-738/es/contenidos/noticia/inkesta_soziol_2012/es_berria/berria.html Retrieved 30 November 2012.

English translation by: Piotr Szczepankiewicz. Translation update: Nicole Nau/Michael Hornsby.

back to top